The (evolving) art of war

In new book, political scientist Taylor Fravel uncovers the modern history of Chinese military strategy.

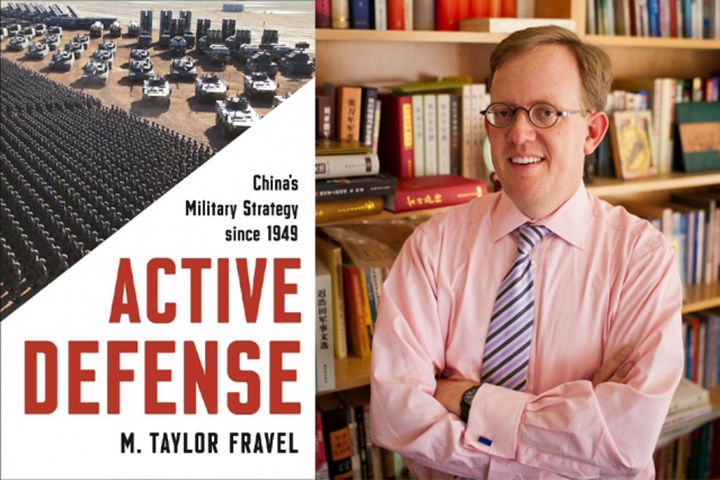

Taylor Fravel and his new book, “Active Defense: China's Military Strategy Since 1949.”

Image: MIT News, Taylor Fravel and Dominick Reuter

In 1969, the Soviet Union moved troops and military equipment to its border with China, escalating tensions between the communist Cold War powers. In response, China created a new military strategy of “active defense” to repel an invading force near the border. There was just one catch: China did not actually implement its new strategy until 1980.

Which raises a question: How could China have taken a full decade before shifting its military posture in the face of an apparent threat to its existence?

“It really comes down to the politics of the Cultural Revolution,” says Taylor Fravel, a professor of political science at MIT and an expert in Chinese foreign policy and military thinking. “China was consumed with internal political upheaval.”

That is, through the mid-1970s, leader Mao Zedong and his hardline allies sought to impose their own visions of politics and society on the country. Those internal divisions, and the extraordinary political strife accompanying them, kept China from addressing its external threats — even though it might sorely have needed a new strategy at the time.

Indeed, Fravel believes, every major change in Chinese military strategy since 1949 — and there have been a few — has occurred in the same set of circumstances. Each time, the Chinese have recognized that global changes in warfare have occurred, but they have required political unity in Beijing to implement those changes. To understand the military thinking of one of the world’s superpowers, then, we need to understand its domestic politics.

Fravel has synthesized these observations in a new book, “Active Defense: China’s Military Strategy since 1949,” published by Princeton University Press. The book offers a uniquely thorough history of modern Chinese military thinking, a subject that many observers have regarded as inscrutable.

“One way to understand how great powers think about the use of military force is to examine their [formal] military strategy,” Fravel notes. “In this respect, China has not been studied as thoroughly or systematically as the other great powers.”

Rethinking Mao

Fravel’s book examines military thinking during the entire length of the People’s Republic of China, dating to 1949, when Mao led the communist takeover of the country. China was not at that point regarded as a serious military power, although Fravel notes that the country’s leaders were giving the idea of becoming one serious thought back then.

“I think some people might be surprised to learn that China has been dedicated to building a modern military, and thus thinking about strategy, since the birth of the People’s Republic,” Fravel says.

As Fravel sees it, based on a significant amount of original archival research, there are nine times in modern China’s history when the government has issued comprehensive new military strategies. These formal strategic plans, he thinks, are critical to understanding what Chinese leaders have thought about military force and how to use it.

“It’s an articulation of principles that should guide subsequent activities,” Fravel says.

Of these nine strategies, Fravel finds three to be particularly significant: Those issued in 1956, 1980, and 1993. The first of these articulated a posture of forward defense meant to insulate the country from invasion by, principally, the U.S.

By the 1960s, however, the country had shifted toward a different military posture, one more in line with Mao’s own thinking, which featured an emphasis on guerilla-style retreat and concession of territory in the face of a potential invasion. The idea, deployed by Mao in China’s civil war in the 1930s, was to wear an enemy down over time while providing elusive targets for opponents.

The Soviet massing of military forces just outside China in the late 1960s raised concerns that it might be better to pursue a more “active defense” — and thus the title of Fravel’s book — in which China positioned its armed forces to contain enemies near the border. But given all the internal political conflict (and leadership purges) within China, this shift did not gain enough traction to be implemented in the 1970s. Moreover, as a distinct change from Mao’s ideas, the notion of active defense required considerable political unity to be implemented.

“In that sense, it was profoundly different, and perhaps challenging to pursue,” Fravel says. “They had to de-emphasize one of Mao’s core strategic principles.”

Still, the new strategy became official policy, and remained such for over a decade — until Chinese military leaders watched the 1991 Gulf War on television and recognized that the new era of precision aerial warfare demanded another shift in strategy for them as well.

“I think in many countries, the Gulf War catalyzed a complete rethinking of warfare in very short order,” Fravel says.

And yet, even as this was occurring, China was experiencing yet another moment of internal political division, following the Tianamen Square massacre of 1989. It took another year or two, and a new internal political consensus, before China could develop a new, contemporary strategy for fighting high-tech wars.

“What they wanted to do was really challenging,” Fravel says, noting that the new strategy requires complex coordination of different military domains — air, sea, and land — which had not previously been unified.

The nuclear exception

China’s 1993 statement of strategy remains a guidepost for its current military thinking. However, as Fravel notes, there is one area of military force — nuclear weapons — which is an “exception to the rule” he postulates about policy following unity. China has had nuclear weapons since the 1960s, while always considering them a deterrent to other countries, and not threatening first use of them.

“When you look at the nuclear domain, they’ve basically had the same strategic goal since testing their first device in 1964, which is to deter other countries from attacking China first with nuclear weapons,” Fravel says. “It’s also the one element of defense strategy never delegated by top party leaders. It was so important to them, they never let go of the authority to devise nuclear strategy.”

Other scholars regard “Active Defense” as a significant contribution to its field. Charles Glaser, a professor at George Washington University, states that Fravel “contributes significantly to our understanding of the evolution of China’s military strategy, and offers insightful theoretical arguments about civil-military relations.”

Avery Goldstein, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, calls the book “an impressive achievement” and notes that Fravel “deftly draws on a wide range of literature about influences on military strategy” as well as “newly available sources of evidence” from historical archives.

For Fravel’s part, he says that identifying the strong pattern leading to changes in China’s military strategy will help as a guide to the future, as well.

“China is a country we know less about, in the study of international politics, than the other great powers,” Fravel says. “If there is a significant shift in the kinds of warfare in the international system, then China would be more likely to consider changing its military strategy.”